It was a typically sweltering summer day in Canton, Ohio on June 16th, 1918, but it hadn’t stopped an estimated 1,200 locals, bolstered by a healthy contingent of press, from gathering in a city park. Nor had it stopped the day’s speaker, former 4-time Socialist candidate for President Eugene Debs, from wearing a heavy tweed jacket and buttoned vest, sweating profusely as he spoke. At 62 years of age, Debs had barely recovered from an illness in time for his midwestern anti-war speaking tour and looked worse for the wear. His audience was a Socialist convention picnic and federal agents wandered through the crowded, randomly demanding draft cards.

Debs, always the political firebrand, heaped praise on the Bolshevik Revolution and defended three local Socialists who had been recently imprisoned for speaking out against the war. “They have come to realize,” he intoned, “that it is extremely dangerous to exercise the constitutional right of free speech in a country fighting to make democracy safe in the world.”

Two weeks later, Debs would find himself arrested under the same charges and become the most well-known defendant against the recently-passed Sedition Act.

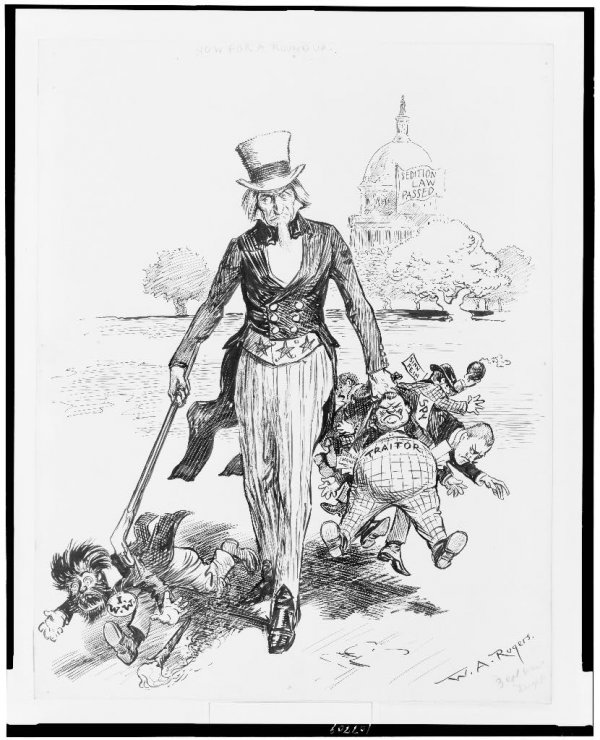

Uncle Sam picks up a variety of individuals – an IWW supporter, a Sinn Fein activist and a “traitor”

While the Sedition Act of 1918 – and it’s precursor, the Espionage Act of 1917 – most assuredly had their roots in America’s involvement in the Great War, President Woodrow Wilson’s interest in far-reaching legal authority related to the domestic end of national security pre-dated the American declaration of war. In late 1915, as Europe’s war raged on, Wilson delivered his State of the Union, declaring:

“There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt … Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out.”

Although Wilson’s Democrats held total control in Washington, including a more than two-to-one advantage in the House, Congress was less than eager to grant nearly unlimited censorship and intelligence power to the hands of the executive branch. While there was most certainly an espionage crisis within the country as German agents were starting hundreds of industrial fires in New Jersey alone, the proposed Espionage Act wasn’t directed against outside agitators but domestic opponents of American neutrality and Wilson administration policies. Even the eventual U.S. entry into the war didn’t make the Espionage Act’s passage any easier, with the Democrat Senate still only managing to pass the legislation by one vote in June of 1917 and only after stripping provisions allowing for the suppression of the press.

Relatively few major publications sided against the Espionage or Sedition Acts

With the Espionage Act’s passage, it was now a crime to “interfere with the operation or success of the armed forces of the United States or to promote the success of its enemies.” How either part of this phrase could be interpreted was left nebulous at best, but the consequences were severe – conviction would lead to a sentence of 30 years imprisonment or death.

The targets of the Espionage Act were clear very quickly – naturalized German-born citizens, pacifists, members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Socialists. Prominent labor and Socialist leaders found themselves jailed for their anti-war speeches and the Wilson administration found loopholes over their inability to censor war-time press, particularly by the use of the U.S. Mail which was run by a Wilson ally, Albert S. Burleson. Burleson had already made a name for himself by segregating the postal service and firing black employees in the South, but now Burleson was gaining national exposure for his aggressive enforcement of the Espionage Act. Burleson was able to stop mailing numerous pacifistic and Socialist publications and displayed such zeal – without a clear code of conduct – that famed Judge Learned Hand deemed Burleson and the Espionage Act were threats to “the tradition of English-speaking freedom.”

Despite the supposed limits on censorship, the Espionage Act found ways of imposing itself on all forms of media. The feature-length film “The Spirit of ’76“, depicting a highly fictionalized version of American independence, put the film’s producers in the Act’s crosshairs. The film depicted a series of over-the-top British atrocities against American civilians, including a physical attack on Benjamin Franklin by King George III. While the film was clearly made to be a pro-war, pro-American movie, it was deemed to have violated the Espionage Act by defaming an American ally, thus inhibiting the war effort. Nor was the film’s case helped by the fact that the main producer, Robert Goldstein, was a German-born Jew. Goldstein received a 10-year sentence (commuted down to three) and a fine of $5,000.

A lot of members of the press claimed they were protecting free speech by siding with the Acts that were limiting it

All of this wasn’t enough for the Wilson administration. Wilson wanted to expand the scope of the Espionage Act to cover “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the United States government, its flag, or its armed forces. And Wilson wanted to settle the dispute over the powers of the Postmaster General and U.S. Mail by consecrating what Burleson was already doing, legal objections or not. At the same time, Wilson hoped to forestall the desire of some of his congressional allies to create a civilian court-martial process to try U.S. citizens born in foreign countries. High-profile cases of the use of the Espionage Act like that with industrialist William C. Edenborn, a naturalized citizen from Germany, could produce challenges that could undermine the entire Act. Edenborn, a major southern business figure, apparently had mocked the threat of Germany to the U.S. while at his railroad business in New Orleans. Federal agents arrested the well-connected Edenborn, but didn’t end up pressing charges, fearing the legal and political consequences of either outcome – some demanded the German-born magnate be kicked out of the country; others saw the case as a clear-cut violation of the 1st amendment that the federal court would easily lose in court. 1,500 others weren’t as lucky as Edenborn as they were prosecuted using the Espionage Act, with over 1,000 of those being convicted.

Eager to resolve these and other issues the Espionage Act had encountered, a series of amendments were introduced in the spring of 1918, being commonly known as the Sedition Act, even though the legislation in question was not a separate Act. The legislation carried the provisions Wilson wanted in terms of language restrictions and the powers of the Post Office, with little organized public opposition to the bills as it’s proponents noted that the amendments were only active “in times of war.” In the Senate did Wilson find some political opposition on the grounds of free speech, largely from Progressive Era Republicans. While the legislation passed 48 to 26, many echoed the words that former President Teddy Roosevelt wrote against the Act, stating:

“To announce that there must be no criticism of the President, or that we are to stand by the President, right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but is morally treasonable to the American public. Nothing but the truth should be spoken about him or any one else. But it is even more important to tell the truth, pleasant or unpleasant, about him than about any one else.”

American op-ed cartoons of the time

The Sedition Act had won in Congress and in the court of public appeal. But it would face one last series of battles – in actual court.

The passage of the Sedition Act had come with merely months left to go in the Great War, meaning that while many individuals found themselves arrested due to the Act, the process of trials and appeals pushed most cases into 1919, past the supposed enforcement period since, on paper, the Act was only valid when the U.S. was in a state of declared war. Such a passage of time could have resulted in the courts reasonably interpreting the Acts as unconstitutional or the sentence unduly harsh – they did not. Instead, the Supreme Court largely sided with the Administration over the legality of the Espionage and Sedition Acts. The most famous of these cases, Schenck v. United States, involved punishing one member of a Philadelphia Socialist Party organization for printing and distributing 15,000 leaflets to men called up for the draft, urging them not to report. The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled in favor of the verdict and sentence, declaring in the words of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes that:

“The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. … The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.”

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes – looking like he’s about to murder the cameraman

The “clear and present danger” doctrine would become the basis for most of the court verdicts upholding the Espionage and Sedition Acts, but the interpretation of what constituted “clear and present danger” could not be defined, and even Holmes disagreed with the Supreme Court’s similar rulings using the doctrine. The same year as Schenck, Holmes dissented in Abrams v. United States – a case of leaflets thrown from a building denouncing the U.S. intervention in the Russian Civil War – stating that there was no basis in believing the actions of the defendant could been seen as a “clear and present danger.” The prosecution threw Holmes own words back at him, prompting Holmes to issue another famous phrase that became a doctrine, the “marketplace of ideas” in which the Justice said: “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

With the war over, and the Acts successfully defended in court, there was little appetite for keeping the most controversial aspects of the Acts on the books or fully enforcing many of the sentences. Wilson would pardon or commute 200 individuals in 1919 and Congress would repeal the Sedition Act at the end of 1920. The Espionage Act remains active today, although most cases involving charges in the modern era have resulted from foreign espionage – far from the initial motivation for the original Act in 1917.

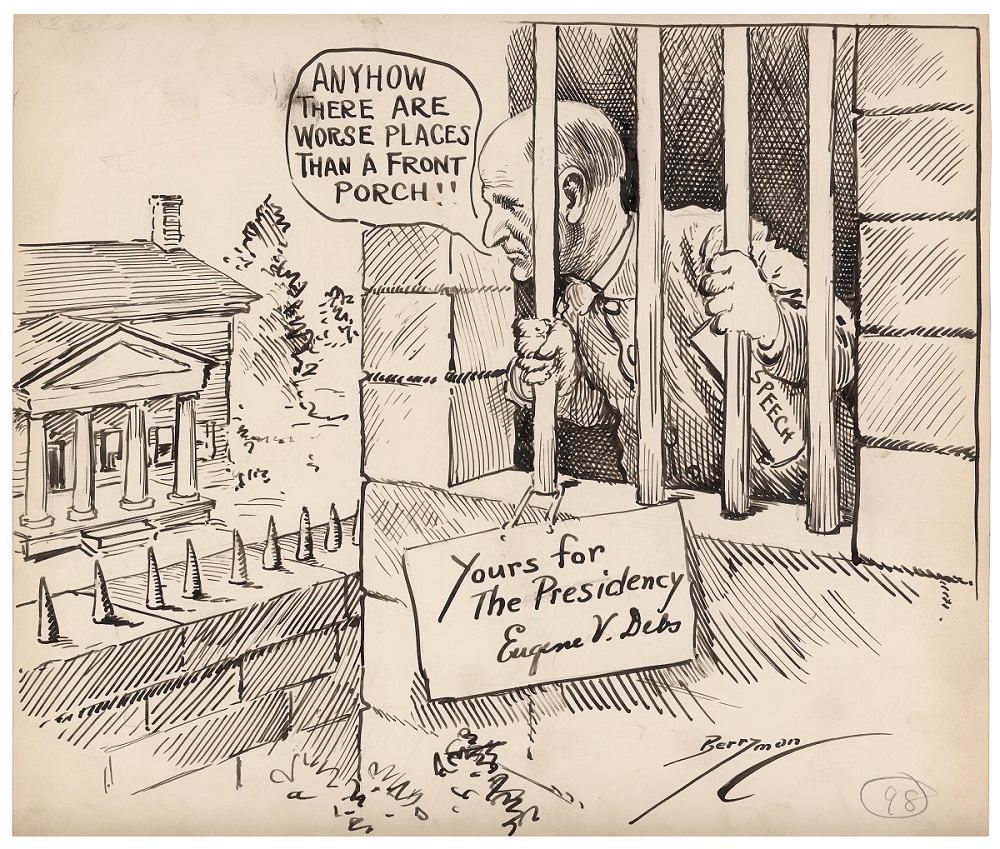

For Eugene Debs, there was little leniency and even fewer apologies from the man himself. Debs basically represented himself at his trial, garnering a sentence of 10 years in jail. He managed to appeal the verdict all the way to the Supreme Court, but the Court declared his case was the same as Schenck v. United States, meaning there was no legal challenge to his sentence. Debs would run for president a fifth time, all while in jail throughout the 1920 election, gaining 3.5% – a drop from the 6% he received in his last presidential run in 1912.

Debs ran for president from jail and spent most of the campaign attacking outgoing President Wilson instead of the actual candidates running

It would take a change in administration for Debs to get out of jail, as President Warren Harding commuted Debs’ sentence to time served in December of 1921. Wilson had been encouraged to pardon Debs, but with Wilson initially attempting to seek a third term – or more realistically, Edith Wilson trying to get her husband another term, given that Wilson suffered a stroke in 1919 that rendered him largely incapacitated – there was no interest in easing off on Debs. “This man was a traitor to his country,” Wilson supposedly told his secretary.

Absolutely stunning essay. I like and appreciate how easily one can see the parallels between the Wilson regime and the present attempt by Democrats to create a authoritarian government. And make no mistake about it, Democrats were authoritarian then, just as they are now.

Shameless — a Benghazi style select committee should help get to the bottom of this. The time frame should work through the next election.

Oliver Wendell Holmes reputation, like Wilson’s, deserves a much harsher evaluation than he has received over the years, see Buck v Bell; in which the Court ruled that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the intellectually disabled, “for the protection and health of the state” did not violate the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution