The retreat was slow, deliberate, and disciplined over the mountains leading from the Azerbaijani village of Dilman on April 15th, 1915. For a conflict that already had claimed or maimed millions of combatants, the men of the Turkish 1st Expeditionary Force were relatively unscathed. Few of the Ottoman regulars had lost their lives. But their conscripted Kurdish cavalrymen were less fortunate – their entire force of nearly 12,000 men had either been killed or deserted.

The objective had been an indirect strike at Russian and British colonial influence through an invasion of Persia. The Great War was further becoming a world war.

—

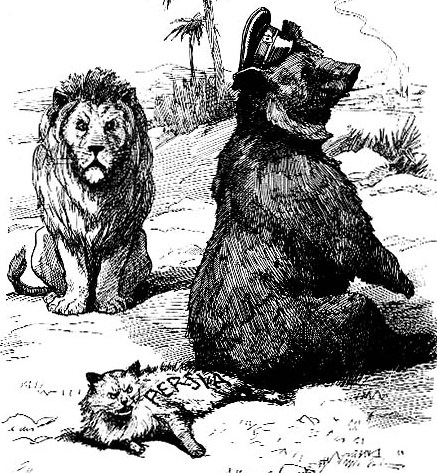

The Great Game, summarized in a 1911 cartoon: “If we hadn’t a thorough understanding, I (British lion) might almost be tempted to ask what you (Russian bear) are doing there with our little playfellow (Persian cat)”

By the spring of 1915, it was already clear that this was no longer just “Europe’s war.”

The British and French had been rushing to outdo themselves in devouring German African territory merely days after the start of hostilities. German and British naval units had fought around the globe, dueling at Coronel off of Chile and at the Falkland Islands. And Japan had entered in the war in its first month, ensuring that some of the earliest land battles to determine the control of Europe would be fought by Japanese troops in Chinese cities against German forces.

Persia was neither a colonial conquest nor even a willing belligerent. Rather, what is now modern Iran sat at a curious nexus; right at the periphery of the Ottoman, Russian and British empires – too distant to be completely dominated by any of their foreign neighbors, but too weak to prevent their territory from becoming a battleground of armies and ideologies.

The Russo-British Persian Pact of 1907 – despite being an independent nation, Russia and Britain divided up control of Persia, leaving a small “buffer” state supposedly free of foreign intervention

For a century, Persia and the rest of Central Asia had been part of Russia and Britain’s “Great Game.” As the Tsar’s armies marched into the Caucasus and British regulars repeatedly attempted to quell the rebellious Afghan/Indian frontier, Persia became a political and territorial demarcation line. With the rise of Imperial Germany as the new foremost foreign policy concern for both Russia and Britain, the two empires negotiated an end to the Great Game with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Entente, formalizing their spheres of influence. Persia was divided into three sections – a Russian north (to prevent Persian influence of Kurdish, Azerbaijani or Armenian rebels), a British south (to ensure shipments of oil that fueled the British fleet), and an buffer zone in the middle.

The Treaty satisfied Russian and British interests – and completely ignored the Persians.

Ahmad Shah Qajar – the last ruler of the Qajar Dynasty, Ahmad was a weak, ineffective leader who stayed in power precisely because he didn’t interfere with the intentions of the Russians, British, Turks, or the Persian Constitutional revolutionaries

Like the neighboring Ottoman Empire, Persian political affairs were drowning in a morass of issues that continue to haunt Middle Eastern states to the modern era – military and financial weakness, an archaic monarchy, nonexistent legislative bodies and a vocal religiously extremist minority set on violently restoring Islamic principles.

Persia was technically an independent nation, ruled by the Qajar Dynasty since the late 1700s. Yet between Russian and British meddling, and numerous rebellious semi-nomadic tribes, the Qajars functionally controlled little of the country. What influence the Qajars did have came financed by their would-be colonial overloads. The Qajars borrowed millions of dollars from the Russians and British to cover the costs of their lavish royal lifestyle and the central government. In return, much of the taxation in the major cities was run directly by foreign powers – the Persians had basically outsourced their own governance.

How Swede It Is: meet Swedish Major Harald Hjalmarson – the head of the Persian military. The Persians chose Sweden to be their military benefactor and much of the officer corps of the Persian Army was Swedish

By 1906, what there was of a Persian educated elite was in full rebellion against the Shah. 12,000 young men, mostly students, gathered at the British Embassy in Tehran, protesting the lack of a parliament and British control of Persian taxation. As revolutions went for the era, it was swift, bloodless, and surprisingly effective. Within mere months, the aging Shah agreed to a parliament, held elections, and witnessed the newly enshrined parliament (or majles) usher in a constitutional monarchy that severely limited royal powers.

The Persian majles was determined to chart a new course away from Russia and Britain – one that would lead indirectly into the arms of the Central Powers.

—

The Persian Gendarmerie: a 6,000 man force the represented about the only centralized fighting force completely under Tehran’s control

Despite great promise and political unity (at least in Tehran), the Persian Constitutional Revolution quickly fizzled.

The ruling Qajars rebelled – as did the variety of ethnic tribesmen the Oajars relied upon to provide what military force Persia could muster. The majles successfully managed to remove the Shah from power, placing his 11 year-old son Ahmad Shah Qajar on the throne instead. The little cohesion the Qajars had given to Persia nearly completely disappeared – the tribesmen began to seek support from Russian, British, Ottoman or German sources, holding no favor for the majles-dominated child Shah.

Mired in debt, the nation was forced to even outsourced their military leadership to a foreign power – the fellow neutral state of Sweden. Why the Swedes? The Persians wished to import European military tactics without being caught in the growing tension between the Entente and Central Powers. Major Harald Hjalmarson was quickly promoted to General and given the command of the 6,000-man Persian Gendarmerie. Hjalmarson had to contend with minimal munitions (12 machine guns for his entire army!) and the reality that they were outnumbered by tens of thousands of irregular Persian forces, militiamen in essence, whose loyalty was spotty at best.

Andranik Ozanian (center) – one of the most prominent Armenian military leaders

Persia was far from ready to enter any war, let alone defend itself. But the war would come to them.

—

As the Great War reached the Middle East, Russian and British designs on Persia had to contend with two new players – Germany and Turkey.

With the Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient (Intelligence Bureau for the East) opening on the eve of hostilities, German provocateurs were determined to ferment revolt anywhere they could in the colonial possessions of their enemies. German agents like Wilhelm Wassmuss, soon to be known as “Wassmuss of Persia” in an obvious attempt to copy T.E. Lawrence’s media-driven “Lawrence of Arabia,” supplied Persia’s rebellious militiamen with arms and anti-British propaganda. Efforts like Wassmuss’ were of limited impact. Rather than turn the militias further against the British, they cemented the tribal belief that Ahmad Shah and Tehran were powerless in their own domain.

War by Hand – the picture quality isn’t very good, but these Armenians are making bullet casings by hand during the Siege of Van

If German interest in Persia was merely strategic, Turkey’s interests were much more ideological.

Enver Pasha, one of the three members of Turkey’s ruling elite and last seen in this series sending 140,000 Ottoman troops to their death or captivity against the Russians, saw Persia as another front in his quest to unite all Turkic peoples under the Ottoman banner. Enver was a die-hard believer in Turanism – a racial political belief that all Central Asia peoples should be ruled together. Enver saw the Great War as a pretext for what would amount to an ethnic war – and rebellious, non-Turkic minorities like Armenians or Assyrian Christians could either submit or be destroyed.

Wassmuss of Persia – Germany’s “Lawrence of Arabia”, Wilhelm Wassmuss convinced the Intelligence Bureau for the East that he could incite a rebellion in Persia against the British

The Turkish 1st Expeditionary Force would be the vanguard of Enver’s ethnic rebellion. Marching into Persian Azerbaijan, the 1st would drive the Russians out of northern Persia, rally the Turkic people to the Ottoman cause, and then possibly strike into the heart of the Russian Caucasus. It was essentially the same strategic plan that Enver had launched against Sarikamish in January, only with an army a fraction of the size.

At Dilman, Enver would get his ethnic war. But he wouldn’t like the outcome.

—

For a battle that was ostensibly fought between Turks and Russians, the initial invasion of Persia in April of 1915 was mostly a fight between Kurds and Armenians.

Both the Kurds and Armenians had been repressed minorities within the Ottoman Empire. But where Constantinople had co-opted the Kurds into the highest levels of the Ottoman government by the late 1800s, the Armenians remained on the outskirts. Decades of violent rebellion had placed the Armenians firmly into Russia’s camp, with the ranks of Armenian volunteers swelling once the Turks had declared war. Led by the veteran rebel fighter Andranik Ozanian, known simply as Andranik, 1,200 Armenian fighters were a large part of what remained of the Russian presence in northern Persia.

The Siege of Van: the defeat at Dilman, coupled with Turkish frustration with Armenian rebels resulted in the assault against the city of Van. Turkish forces were driven off, but not before they killed 55,000 civilians

Opposing Andranik were 25,000 Ottomans, 12,000 of which were irregular Kurdish cavalry. These weren’t untrained, unreliable militiamen. Since the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, such Kurdish horsemen were given lavish training and equipment (at least by comparison to the organized forces of other ethnic minorities). And Kurdish cavalry had often been used as “shock troops” by the Ottomans against rebelling Armenians. If Andranik’s men didn’t have enough reasons to fight, the presence of the Kurdish cavalry gave them another.

With the bulk of the Russian forces in the Caucasus stationed closer to the Black Sea, not Persia – the Ottomans easily captured Dilman by April 14th. In hopes of turning a solid victory into a larger rout, the Ottomans pressed their advantage in a night-time raid by their Kurdish cavalry. They achieved their desired rout – only on the wrong side. 2,000 Kurds were ambushed by Armenian volunteers and butchered, their mutilated corpses a grisly discovery for the remaining Ottoman troops the next morning. The defeat sent a ripple down the line of Kurdish troops. Within days, the vast majority of the 12,000 Kurds sent to Dilman deserted.

Their forces depleted, and with Russian reinforcements arriving, the Ottoman invasion of Persia looked to be over before it ever truly began.

—

Kurdish Cavalry – the Ottomans had frequently used Kurdish soldiers to do their dirty work against the Armenians. That history would be the undoing of the 12,000 Kurdish cavalry members who marched into Persia

Conspicuously absent in the first campaign to decide the fate of Persia in the Great War were the Persians themselves.

The Persian decision to outsource the nation’s military leadership to Sweden had an unintended consequence – it placed Persia’s government firmly in the camp of the Central Powers. Most of the Swedish officer corps was German trained and aligned. Coupled with the nation’s sense of powerlessness at the hands of the Russians and British, native Persian officers would soon be leading the Gendarmerie against the Entente.

By November of 1915, Persia’s division had spilled into open conflict. Gendarmerie led assaults against Russian Cossacks and British-aligned tribesmen. Persian ministers were negotiating with German representatives. Eager to quiet the rebellious Persians, the Russians marched on Tehran. Leading 15,000 men, a mixture of the Gendarmerie, loyal tribesmen and Ottoman soldiers, Ahmad Shah Qajar attempted to hold the capital. His make-shift force was easily brushed aside. Now in control of Tehran, the Allies forced the child-Shah to appoint a pro-Entente government.

Persian Cossacks – while Russian Cossacks are more famous, Persia employed thousands of Cossacks during the Great War as well

What was just another front in the Great War to the European powers had now become a civil war in Persia.

—

Such a fate for the Persian front was unknown for the Turkish survivors marching back in defeat in April of 1915. For the second time in less than four months, Enver Pasha’s grandiose dreams of a Pan-Turkic Empire in Central Asia had collapsed. And once again, Enver blamed the outcome on his own Armenian population.

Armenian disloyalty could only be repaid in blood – blood shed at the front lines of the Empire’s war with Russia. Forcible conscription efforts increased throughout the Armenian populace. At the city of Van, home to 110,000 Armenians and 180,000 Turks, Ottoman commanders demanded 4,000 soldiers be immediately conscripted from the city. To the Armenian population of the city, the order was a pretext to rounding up able-bodied males for execution, as the tactic had been done in other, smaller, Armenian communities. The city elders of Van attempted to compromise, suggesting they offer 500 men and money.

Kurdish troops at the Siege of Van – the commander of this Kurdish unit was a Venezuelan, Rafael de Nogales Méndez, a 19th/20th Century soldier of fortune who we will re-visit later in the war

The Ottoman commander was not satisfied. If the Armenians did not produce 4,000 men, or attempted to resist in any way, the Ottoman commander insisted “I shall kill every Christian man, woman, and” (pointing to his knee) “every child, up to here.”

On April 20th, 1915, as Ottoman forces were still retreating from Persia, the forcible conscription from the city of Van was disorganizing into chaos. Ottoman troops were shooting civilians they deemed as interfering, and soon the Armenian quarter of the city was under siege. For the next month, 1,300 Armenian defenders attempted to protect as many civilians as they could. 55,000 fell into Ottoman hands and were killed.

You Do Have to Live as a Refugee – an estimated 810,800 Armenians survived the attempted genocide, escaping to Russia, the Middle East or Europe

The Turkish policy against the Armenians since Sarikamish was now out in the open. No longer was forced conscription the Ottoman remedy to Armenian dissent, but forced deportation. Millions of Armenians began to flee the Ottoman advance.

If Enver Pasha’s Turanism could not be realized outside the Ottoman Empire’s borders, he would ensure that it at least would within his borders. An estimated 1.5 to 2 million Armenians would pay the ultimate price for his vision.

Pingback: The Barren Crescent | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: A League of Their Own | Shot in the Dark